I was about seven the first time I saw my father teach. I sat in the back of the lecture room, scribbling in an examination “blue book.” Every once in a while, I looked up at the people seated near me, unwitting inspiration for my imaginative stories. Next to the blackboard was a tall man, gesturing wildly with chalk in hand, his usually soft voice at full volume as he punctuated his lecture with anecdotes from history. Like a born-again preacher wooing his congregation, my father spoke zealously. His gospel for students? Learn about history in order to understand your grandparents, your parents — and yourselves.

I remember asking him many years ago if he liked his job. He smiled broadly. “What other job would pay me to read books?” But even then, I knew teaching for him was about more than devouring the latest hardcover analysis of political upheaval. It was about translating scholarly ideas into language that could engage the minds of history majors, business majors and college jocks alike. It was about nurturing the worldview of even the most provincial undergraduate student.

Being the child of an academic had unique perks. Like the dinnertime conversations that enlightened my brother, sister and me about American diplomacy after the Second World War. Or the help I got with a high-school research assignment on the Middle East. Of course, there were also drawbacks to growing up in a family headed by a professor. One Christmas, for example, while most families huddled together in front of the TV to watch “It’s a Wonderful Life,” my father summoned all of us for a video double feature: Leni Riefenstahl’s “Triumph of the Will” followed by Charlie Chaplin’s “The Great Dictator.” Somehow, even family gatherings could turn into history lessons.

A lot has happened since Dad picked up his first piece of chalk. Back in 1963, there were no PowerPoint projectors or VCRs in university lecture halls — nor did any PCs grace the desktops in offices. Yet even after these technological advances made their way onto campus, my father eschewed the wizardry of modern academia. He winced at words like “multimedia,” took his sweet time warming up to chalk replacements like dry-erase markers, and staunchly refused to learn how to use a laptop. Having never learned to type, the eccentric professor relied instead on his distinctive longhand to create syllabi and exams, painstakingly writing out words as well as drawing his own maps.

At times an intellectual curmudgeon, he confronted each student essay with a critical eye. But I can think of no better gift for a student than a set of firm expectations based on high standards. Especially when the teacher holds himself equally accountable. Even for courses he taught repeatedly, my father liked assigning new books so that he, too, could be reading and learning alongside his students. By becoming the wise mentor, he kept himself young at heart.

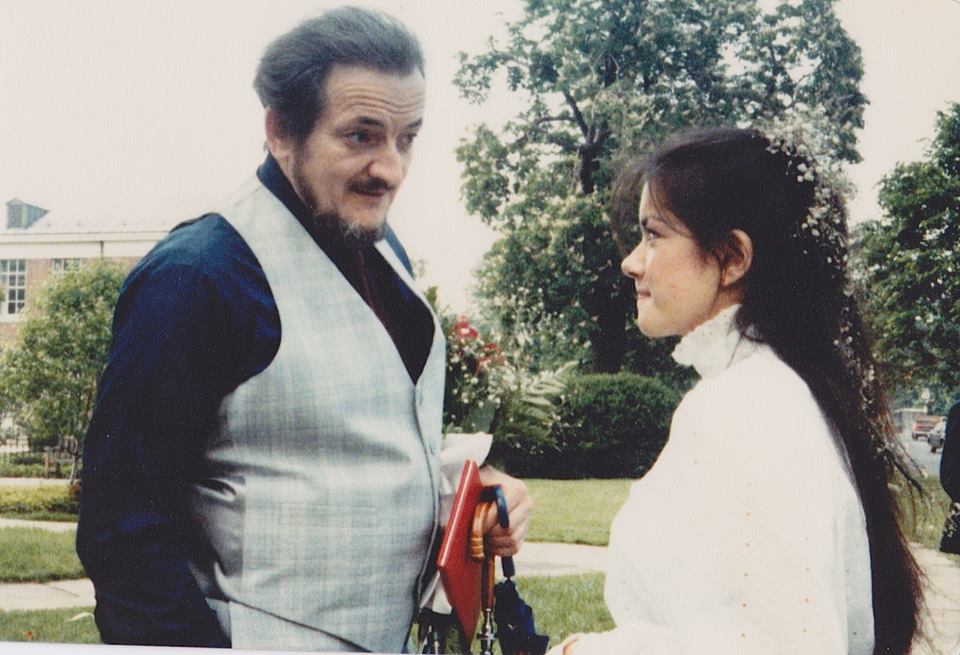

In a few months, the man who fell in love with teaching some forty years ago will retire from the classroom. While the septuagenarian’s body is more than ready to slow down, his mind for recalling dates and events remains razor-sharp — and his appetite for understanding national identities and global affairs, ravenous. Somehow, I just can’t picture the old man on a golf course.

“Those who can, do. Those who can’t, teach.” Or so the putdown goes. But educators can have a profound influence on the consciousness — and conscience — of each one of us. As Henry Adams said, “A teacher affects eternity; he can never tell where his influence stops.”

Originally titled “Great Professors Exert Profound Influence On Us” and published as a “My View” column in the May 7, 2003 issue of The Buffalo News